Oxbridge-Science-Academy.github.io

Coupling

NMR spectra rarely consist of clearly defined single peaks. Rather, peaks are often split into symmetrical patterns (called splitting patterns) such as doublets, triplets and so on – this is the result of coupling. Coupling arises due to the interaction of nuclear spins and is transmitted via the electrons in the bonds between the nuclei. Coupling only occurs between non-equivalent nuclei (nuclei in the same environment do not couple) and 1st year undergraduate work tends to focus on coupling over 1 bond for 13C NMR and over 3 bonds for 1H NMR, although other coupling is also possible.

At this level it is sufficient to state the general rule of coupling to be: “if nucleus A couples to n equivalent nuclei, its peak will be split in a n+1 peaks”. It is important to note that the term “equivalent” here means that the n nuclei being coupled to are equivalent to each other, not that nucleus A is equivalent to these nuclei (equivalent nuclei do not couple to each other).

For example, if nucleus A only couples to 1 other nucleus, its peak will be split into 2 peaks and called a doublet and if it couples to 2 other equivalent nuclei its peak will be split into 3 peaks called a triplet.

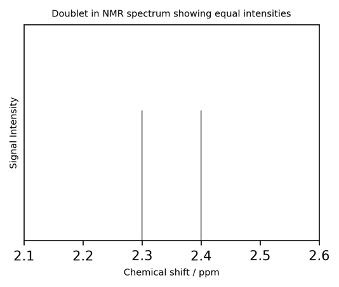

Doublet Case Study

Consider a nucleus A which couples to another nucleus B (and to no other nuclei); both A and B have nuclear spin 𝐼=1/2. In some molecules, nucleus B will be spin down, denoted ↓, and in other cases it will be spin up, ↑.

At this stage it is sufficient to acknowledge the fact that the spin of B will affect the nuclear energy levels in A (and therefore the energy level spacing too) such that when A couples to a spin ↓ B nucleus it will emit a slightly different radio wave frequency than when it couples to a spin ↑ B nucleus.

On average 50% of B nuclei will be spin ↓ and 50% will be spin ↑ and so 50 % of A atoms will emit one radio frequency and the other 50% will emit a different radio frequency. These two different frequencies will result in two different chemical shift peaks but the 50:50 ratio means the peaks will have the same intensity (height). This is a described as having an intensity ratio of 1:1.

TripletCase Study

Consider a nucleus A which couples to two B nuclei (and to no other nuclei); both A and B have nuclear spin 𝐼=1/2. A particular A nucleus in a molecuke could “observe” 3 different spin combinations: ↑↑, ↑↓ ,↓↑, ↓↓

Note that ↑↓ and ↓↑ are equivalent since the two B nuclei are equivalent.

The paired spin situations (↑↑ and ↓↓) will affect the nuclear energy levels the most and so result in the highest and lowest chemical shift values. The opposing spin situations (↑↓ and ↓↑) will not change the nuclear energy levels (spin effects cancel out) and so will result in a chemical shift in the middle of those from ↑↑ and ↓↓. However, because there are two ways to have a opposing spin situation, it is twice as likely to occur and so the corresponding signal will be twice as intense (high) as those from ↑↑ and ↓↓. This 1:2:1 intensity distribution is seen for triplets.

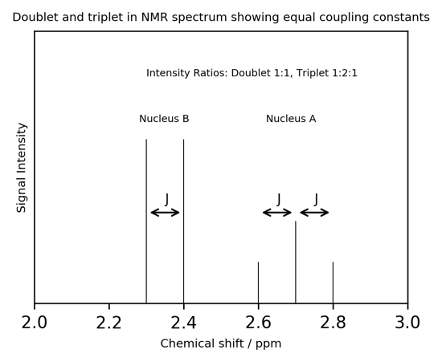

Coupling Constant

An important feature of coupling is the coupling constant, J. This is the difference (in units of frequency) between sub-peaks split by coupling. For example, in a doublet the coupling constant is simply the frequency difference between the two peaks and in a triplet it is the frequency difference between the outer and central peaks.

The theory behind the coupling constant is beyond the scope of this course but it is sufficient to say at this stage that it depends on several factors including the number of bonds over which the coupling occurs and the relative orientation of the bonds (a fact which is exploited for 3D structure determination).

More importantly at this level, if nucleus A has its signal split into sub-peaks with coupling constant J due to coupling with nucleus B, then nucleus B will have its signal split with the same coupling constant J. We can therefore use the value of the coupling constant to determine if two nuclei are coupling to each other and by extension determine their relative positions in the molecule.

Note, it is important to remember that just because two different nuclei exhibit the same coupling constant does not mean they will have the same splitting pattern. For example if 1 A nucleus coupled to 2 B nuclei, the A nucleus signal would be a triplet and the B nucleus signal would be a doublet but the coupling constant would be the same.

Let’s combine the two previous examples and consider an the NMR spectrum which shows a doublet and a triplet. The coupling constants are indicated by the double-headed arrow which is the standard way of showing them on a plot.

It is clear that the coupling constant correspond to 0.1 ppm but such a statement is meaningless as different NMR spectrometer operate at different frequencies. To convert the coupling constant to units of frequency, we first have to find the frequency of the NMR machine. Let’s assume it is 200 MHz, an average value for 1H NMR.

0.1 ppm of 200 MHz:

Hz

This is at the higher end of 1H coupling constants.

Coupling to multiple environments

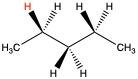

The previous slide will probably have covered everything taught in high school regarding NMR. However, at undergraduate level, we go into more detail. Firstly, we need to consider coupling with multiple groups of non-equivalent nuclei. Consider the molecule pentane and, in particular the two hydrogens on the 2nd carbon. One of these hydrogens has been circled.

The ref proton will not couple to the other proton on the same carbon as they are equivalent. It will not couple to either the 2H on the 4th carbon (as they are equivalent to the 2H on 2nd carbon) and the 3H on the other terminal carbon which are too far away. However, it will couple to the 3H on the terminal carbon and the 2H on the central carbon. One might think the result would be sextet since the proton is coupling to 5 other nuclei. However, as these 2 sets of nuclei are non-equivalent, the result will is more complicated and termed a triplet of quartets. The triplet comes from coupling to the 2H on the central carbon and the quartet from the 3H on the terminal carbon. In reality it may be hard to discern shape of this peak in the spectrum due to overlap. If this is the case, such a peak is called a multiplet.

Compare this to the coupling displayed by a proton on the central carbon. This couples to 4 equivalent protons (on 2nd and 4th carbons), producing a quintet.