Oxbridge-Science-Academy.github.io

Measurement Techniques

Back to Chemical Kinetics Home

Copyright Oxbridge Science Academy 2022

We have already discussed how we can determine the RDS by varying one species’ concentration at a time and seeing how the rate changes. We have also seen how careful choice of plotting will allows us to determine the order of reaction with respect to a particular species (e.g. a plot of ln[X] against time will yield a straight line if reaction is first order with respect to X) However, we should consider how concentration is measured in the first place and the benefits and limitations of common methods. Indeed, if we are unaware of the limitations of a particular method, we make ourselves vulnerable to drawing incorrect conclusions about the data.

You will have come across some techniques for measuring rates such as measuring the quantity of gas evolved or mass change in a reaction but these require the reaction vessel to lose a product(s). We shall look at 3 common techniques:

1.Absorbance of Radiation

2.Conductivity

3.Titration

Absorbance of Radiation

If a species, either reactant or product, absorbs a particular frequency of radiation, we can track its concentration by measuring the transmittance, , at that frequency.The transmittance is the ratio of the intensity (power per unit area) of radiation exiting a sample,

, to the original intensity of the radiation entering the sample,

:

This ratio is easily measurable - all that is required is a source of the radiation and detectors are positioned either side of the reaction vessel which measure the intensity.

However, we also need to relate the transmittance to the concentration of the species of interest. Fortunataley we can do so using the expression:

Where is the molar extinction coefficient which depends on the radiation frequency and absorbing molecule, c is the concentration of the molecule of interest l is path length in the vessel (how far the radiation travels through the medium containing the molecule of interest).

Combining these two expressions for transmittance allow an equation relating a measurable quantity (ratio of intensities) to the variable of interest, concentration:

This method is advantageous because:

-

it is non-invasive - no physical implements, which could affect the reaction, need to be added to the reaction mixture,

-

it is non-destructive - the measured species is not destroyed and so can continue to the react, potentially allowing for the tracking of a multi step reaction

-

a data-logger can record measurements at very high frequency, building up a “real time” picture of the concentration change.

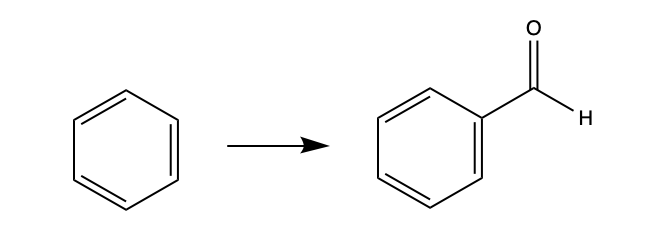

Molecules with bonds like benzene often absorb a specific frequency of UV light and can be tracked with this method. The absorption arises when an electron in a particular ππ molecular orbital is promoted to a higher energy MO. The energy difference between MOs, which depends on the wider ππ bonding structure, will determine the frequency of absorption. It will be different for different molecules so reactant and products can be traced separately. The Friedel-Crafts acylation of benzene is an example of where the would be very useful. The conjugated system of benzene has 6

electrons while benzaldehyde has 8

electrons and a different molecular orbital structure.

Limitations include the complication when multiple species absorb at very similar frequencies and, for sensitive reactions, the addition of UV light could cause unwanted side-reactions by exciting molecules. For example, polymerisation can be induced in some circumstances by irradiation with UV light.

Conductivity

During an aqueous phase reaction, the concentration of charged species may change. For example, if a soluble salt is produced in a reaction, positive and negative ions will appear in solution, changing the solution’s ability to conduct electrical charge, typically quantified by the parameter conductivity, .

The relationship between ion concentration and conductivity is complex, non-linear and depends on ion charge. However, reasonable approximations allow the concentration of a species to be tracked during a reaction.

Like transmittance, this method is non-invasive and non-destructive but it does require there to be ions present in significant amounts and analysis can be complicated by impurities.

Titration

This method is the most time-consuming of the three and is less suitable if very precise measurements are needed. The basic method involves taking samples of a reaction mixture at periods of time after the initation of the reaction and performing a titration to determine the quantity (and therefore concentration) of a particular species. To prevent the reaction from proceeding further while in the titration vessel, it must be stopped (termed “quenching”), often using acid or base.

Each titration provides a “snap-shot” of the reaction mixture at a particular point in time and when they are all combined, a full profile can be seen. Limitations include the fact that the frequency at which samples can be taken is less than for the transmittance or conductivity method and the time-consuming procedure of taking a sample and quenching adds uncertainty to the time we assign to each sample. However, it does allow us to measure reactions the other two methods cannot.